Stateful by Design: The Missing Serverless Abstraction

Serverless removed servers from the developer's mental model, but it also removed state from first-class support. For data-intensive workloads, that tradeoff is increasingly costly. Stateful-by-design removes the fiction that state does not exist. That is the missing abstraction.

Why warm, owned state deserves to be a first-class primitive

Serverless platforms succeeded by making compute stateless, disposable, and elastic. That abstraction removed enormous operational burden, but it also erased an entire class of workloads from first-class support.

For memory-bound, data-intensive, locality-sensitive systems, state is not incidental. It is the workload.

This paper argues that stateful-by-design execution is the missing serverless abstraction, and that treating warm memory and locality as first-class primitives unlocks a more efficient category of systems.

How statelessness became dogma

Serverless did not win because it was fast. It won because it was simple.

Stateless execution eliminated machine management, capacity planning, long-lived processes, and much of the complexity around failure recovery. Developers could deploy code without thinking about where it ran or how many instances existed. The platform handled all of that.

But over time, statelessness stopped being a tool and became a rule. Today’s platforms implicitly assume that if something is stateful, it isn’t serverless. That assumption is increasingly wrong.

Statelessness solved operational pain, not performance reality

Stateless compute is ideal when requests are independent, data is small or remote, cold starts are acceptable, and CPU dominates cost. Many web applications fit this profile well.

But there is a growing class of workloads where these assumptions break down. Consider systems where data volumes reach hundreds of gigabytes to terabytes, where memory bandwidth dominates runtime, where requests are correlated over time, and where data movement costs more than computation. In these systems, statelessness is not neutral; it is actively harmful.

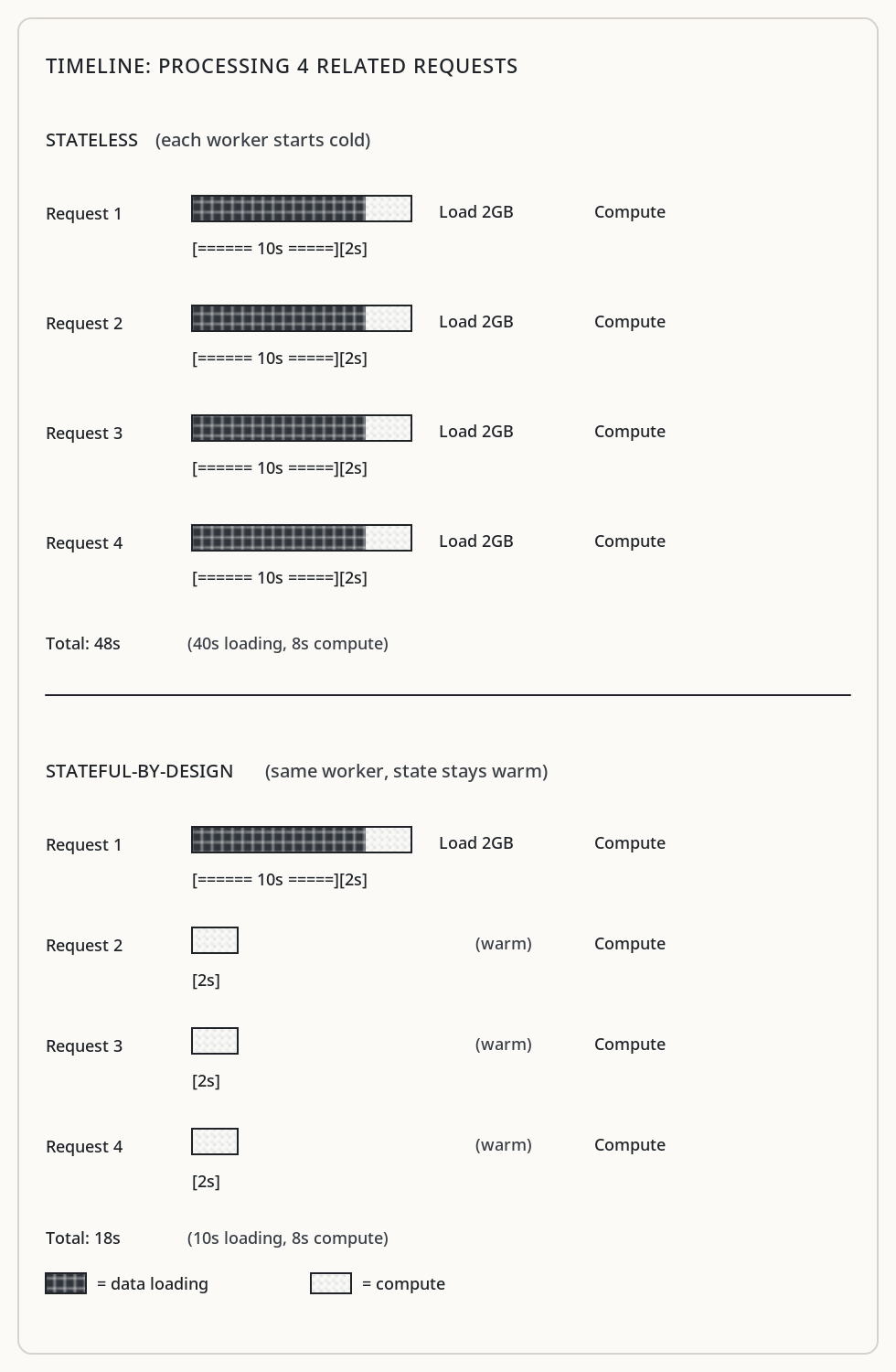

Examples include interactive analytics over large datasets, financial risk and portfolio analysis, matrix and tensor computations, vector search and similarity queries, and scientific simulations. These workloads share common traits: they often read one to three gigabytes per request, run for ten to fifteen seconds, exhibit strong temporal locality, and repeatedly access overlapping data.

Here, recomputing is cheap. Reloading state is not.

The illusion of “stateless, but cached”

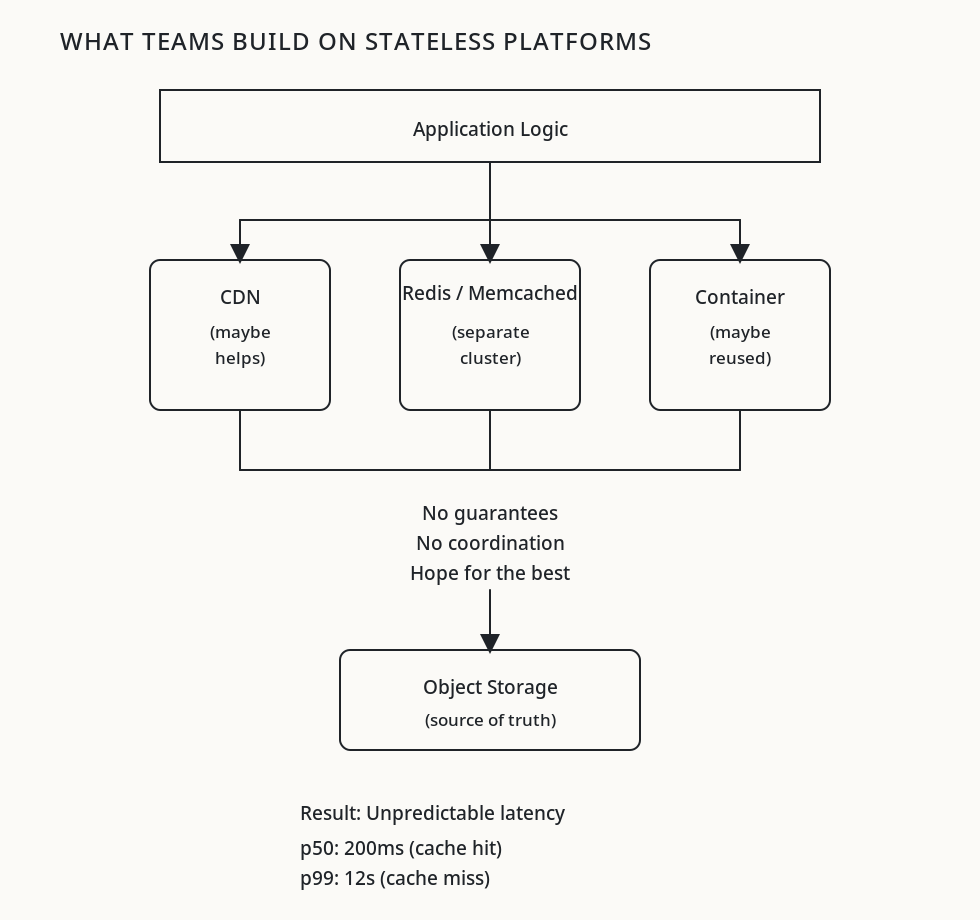

Teams often respond to these performance problems with a familiar refrain: “We’ll keep it stateless and add caching.”

In practice, this usually means object storage with a CDN, Redis or Memcached sidecars, and hoping containers get reused. This is accidental state. It provides no guarantees, weak locality, unpredictable latency, and fragile warm-up behavior. Caching becomes a best-effort optimization instead of a reliable performance primitive.

The problem isn’t that caching doesn’t help (it often does). The problem is that the platform has no model of what state exists, where it lives, or how to schedule around it. State becomes something teams fight to preserve rather than something the platform helps manage.

Making state intentional

A stateful-by-design platform does not pretend state doesn’t exist. Instead, it makes state explicit, bounded, owned, and reconstructible.

Workers are long-lived by design, not by accident. State exists because the platform allows it to exist, and schedules work around it. This is a fundamentally different model from hoping containers stay warm.

What today’s serverless platforms lack is owned, warm state: not global, not infinitely replicated, not ephemeral, but attached to a worker for a meaningful time window. This state might include decoded data structures, memory-mapped files, hot disk blocks, or in-memory indexes. The scheduler knows this state exists and acts accordingly.

Locality as a scheduling primitive

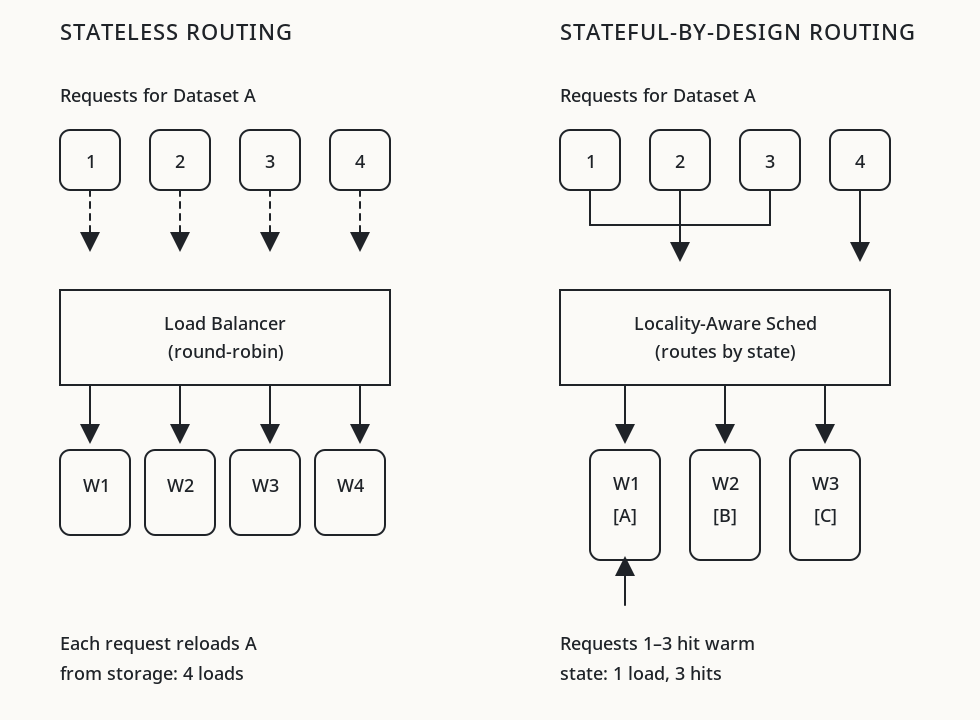

In stateless systems, every request is equal, history is ignored, and locality is accidental. The scheduler optimizes for utilization and availability, treating all workers as interchangeable.

In stateful-by-design systems, scheduling is biased by history. Related requests are co-located. Locality is preserved deliberately. The difference matters: serving two related requests on the same worker can mean the difference between milliseconds and seconds.

This requires the scheduler to maintain some model of what state each worker holds and to route requests toward workers likely to have relevant data warm. This is more complex than round-robin or least-connections load balancing, but the performance benefits for state-heavy workloads can be substantial.

Rethinking failure

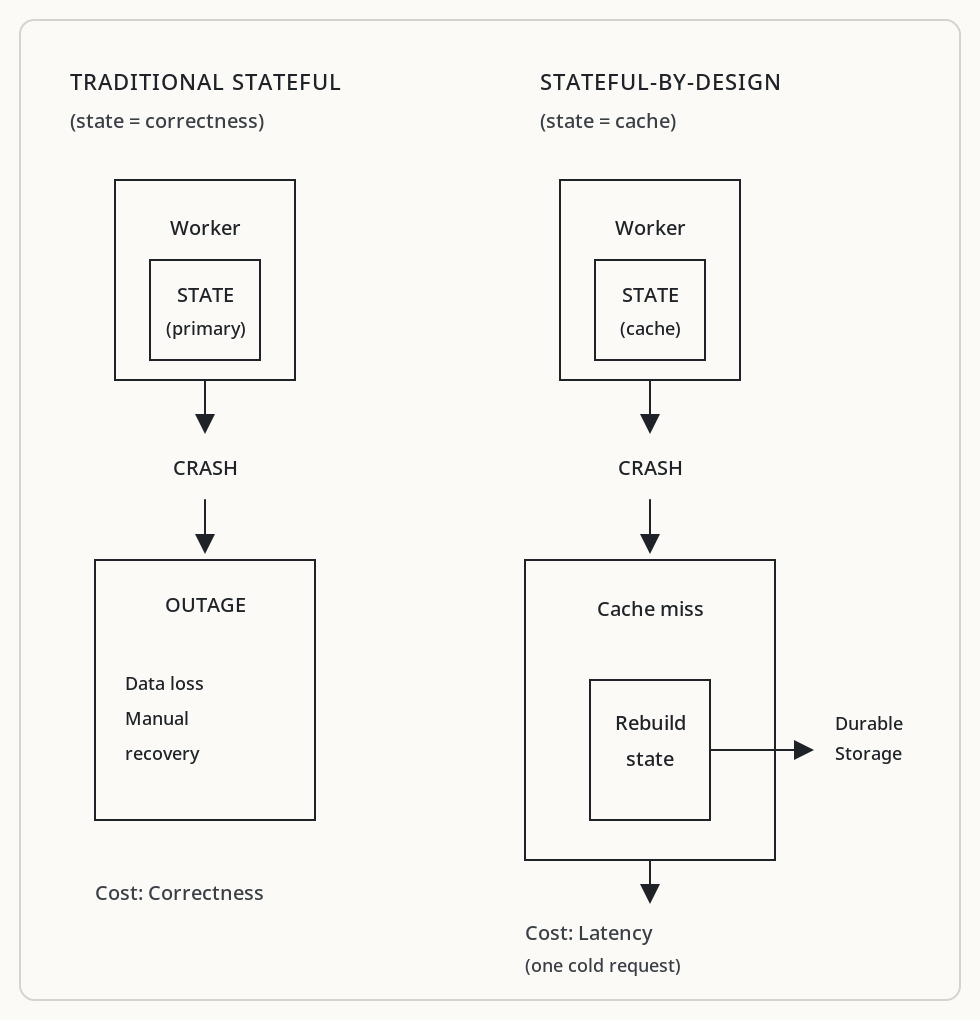

Stateful systems are often criticized as fragile. This is true when state is implicit, when state loss breaks correctness, and when recovery is manual.

In a stateful-by-design system, state is cache-like. Correctness does not depend on it. Failure costs performance, not correctness. A worker crash causes cache misses, not outages. The system can always reconstruct state from durable storage; warm state is an optimization, not a requirement.

This distinction matters. Traditional stateful systems couple state to correctness, which makes failures dangerous. Stateful-by-design systems decouple them, which makes state a performance optimization that can be lost and rebuilt.

This is still serverless

Stateful-by-design does not mean hand-managed servers, manual scaling, or bespoke recovery logic. It preserves core serverless values: no machine management, declarative deployment, automatic retries, and strong observability.

It simply rejects the fiction that state does not matter.

The developer still doesn’t manage machines. The platform still handles scaling and failure. What changes is that the platform also manages locality: routing work to where relevant state already lives, keeping workers alive when their state is valuable, and rebuilding state transparently when workers fail.

Why this abstraction didn’t exist sooner

This model is uncomfortable for platform providers. It reduces worker fungibility, which lowers utilization. It complicates scheduling, which increases platform complexity. It makes capacity planning harder, because workers are no longer interchangeable.

But for users, the tradeoffs often favor stateful-by-design: reduced data movement, improved predictability, and lower total cost for state-heavy workloads.

The abstraction was missing not because it was impossible, but because it optimized for the wrong incentives. Platform providers naturally optimize for their own efficiency. Users need platforms that optimize for workload efficiency.

The natural evolution

As datasets grow faster than memory bandwidth, and as interactive data workloads become the norm, stateless compute stops being the default solution.

The next evolution of serverless is not faster cold starts, more aggressive autoscaling, or smaller functions. It is treating state as a first-class resource.

This doesn’t mean abandoning stateless compute. That model remains ideal for many workloads. It means recognizing that some workloads are fundamentally state-bound, and that pretending otherwise forces teams to build fragile workarounds for problems the platform could solve directly.